Curator Catherine Daunt explores the works of American artists Richard Hunt and Emma Amos, featured in our current free display New acquisitions: Paul Bril to Wendy Red Star, open in Room 90 until 10 September.

Content warning: The blog contains references to racism, slavery, graphic violence and murder.

Paragraph 1

In August 1955, when the now-renowned sculptor Richard Hunt (b. 1935) was a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, another Chicago boy, 14-year-old Emmett Till, was brutally tortured and lynched in Mississippi. Till, who like Hunt was Black, had travelled to the then-segregated southern state to see relatives. While he was there, he visited a grocery store to buy bubble gum and was accused of harassing a young white woman. Till's body was discovered in the nearby Tallahatchie River a week later. He had been abducted, beaten so badly that he had lost one of his eyes, and shot. The woman's husband and his half-brother were arrested and tried for the murder but were acquitted by an all-white jury, only to admit to it four months later when they were protected by the double jeopardy rule. Hunt, like many, was profoundly affected by this racially motivated crime, which gained widespread coverage in part due to Till's mother's decision to show her son's mutilated body in an open coffin at his funeral, photographs of which were circulated by the press. Aged just 19 when the murder happened, Hunt realised that it could have been him, or any other Black boy living in America.

Paragraph 2

A few months later, in the spring of 1956, Hunt produced his first lithographs, which included Prometheus, an impression of which has recently been acquired by the British Museum (above). The print is a direct response to the lynching of Emmett Till, the cri de cœur of a young Black artist who had been among the thousands who viewed his open casket in Chicago and remained haunted by a photograph of Till's mutilated body that he had seen in Jet, a magazine aimed at the African American community.

Paragraph 3

As a metaphor for Till's suffering, Hunt uses the Greek myth of Prometheus, who brought civilisation to humans by stealing fire from the gods. Condemned by Zeus to eternal suffering, Prometheus was bound to a rock and his liver was eaten daily by an eagle (a representation of Zeus), before growing back overnight. The tale of Prometheus has inspired artists for centuries, resulting in some of the most horrifying depictions of human torment in art. Other examples in the British Museum collection include drawings by the Flemish artist Jan Snellinck (about 1544/49–1638) (above) and Swiss artist Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) (below).

In paint, famous examples include Prometheus Bound (1611–12) by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), which is now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. To achieve a realistic depiction of the eagle, Rubens collaborated with the artist Frans Snyders (1579–1657), who was known for his paintings of animals. Snyders' study drawing for the eagle is also in the British Museum collection (below).

Paragraph 4

In Hunt's lithograph, Prometheus is depicted as an emaciated, almost decomposed figure, bound across the chest, with his arms outstretched and a face so damaged it is barely recognisable as human. The eagle, composed of semi-abstract lines and rapid brushstrokes, swoops down from above, its razor-sharp beak pointed toward the figure's liver. Hunt printed this ambitious and powerful lithograph himself rather than working with a master printer, as artists untrained in printmaking often do. He produced just seven impressions, only two of which are in museum collections: the impression at the British Museum and another at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In the same year he also made Hero's Head, a sculpture of Till's deformed face in welded steel. Hunt has gone on to become one of the most important American sculptors and continues to make work today. In 2022 he was the first artist commissioned to create a work for the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago and he has recently designed a sculpture to be installed as a monument at Emmett Till's family home. Prometheus is on display in Room 90 in the exhibition New acquisitions: Paul Bril to Wendy Red Star until 10 September 2023, after which it will be available to view by appointment in the Prints and Drawings Study Room. It is the first work by Hunt to enter the British Museum collection.

Paragraph 5

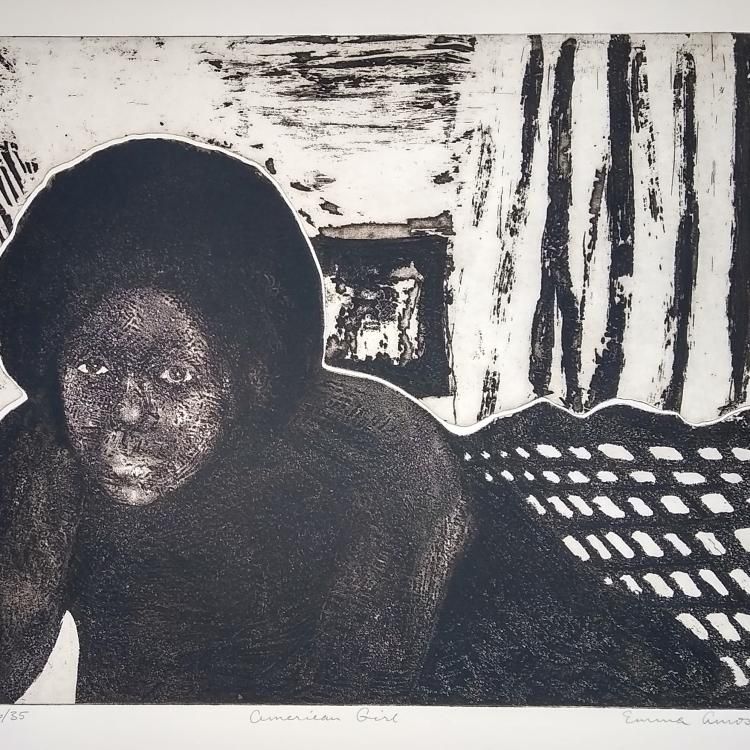

The New acquisitions exhibition also features the work of Emma Amos (1937–2020), another African American artist who was an almost exact contemporary of Hunt's. Amos was born in Atlanta, in the southern state of Georgia, where she attended segregated schools and, like Hunt, was the descendent of enslaved people. In the 1960s, she became a member of 'Spiral', a collective of Black artists based in New York City, and she later joined the Guerrilla Girls, a feminist collective of women artists. Through her art, Amos addressed race and racial inequality throughout her life, particularly focusing on the history of Black people in the US. The exhibition includes two prints by Amos, acquired by the Museum in 2019 and 2020 respectively. The first, titled American girl, is an etching and aquatint made in 1974 (below).

Paragraph 6

Made when the Women's Liberation and Black Power movements were at their height in the US, it is a self-portrait in which the artist fixes her gaze on the viewer. The second (below), made almost two decades later in 1992, is titled Land of the Free and is a colourful monoprint of a map representing an area of the US. It is annotated with names of African and Native American tribes and overlaid with photographic images of Black people living in America, and the details of their lives. It includes a photograph of the artist herself in which she, again, looks out at the viewer. Like much of Amos's work, these prints shine a light on suppressed histories in the story of the US and integrate them into the dominant narrative. A Black woman in America is an American girl and Black and Native American histories in America are American history. The British Museum currently holds four prints by Amos, as well as work by the Guerrilla Girls, all of which can be viewed by appointment in the Prints and Drawings Study Room when not on display.