Patricia Cumper

Playwright, producer and director Patricia Cumper is also a British Museum Trustee. Here, she looks at what Black History Month has meant to her, and how the British Museum can help to tell these stories to the world.

What Black History Month means to me

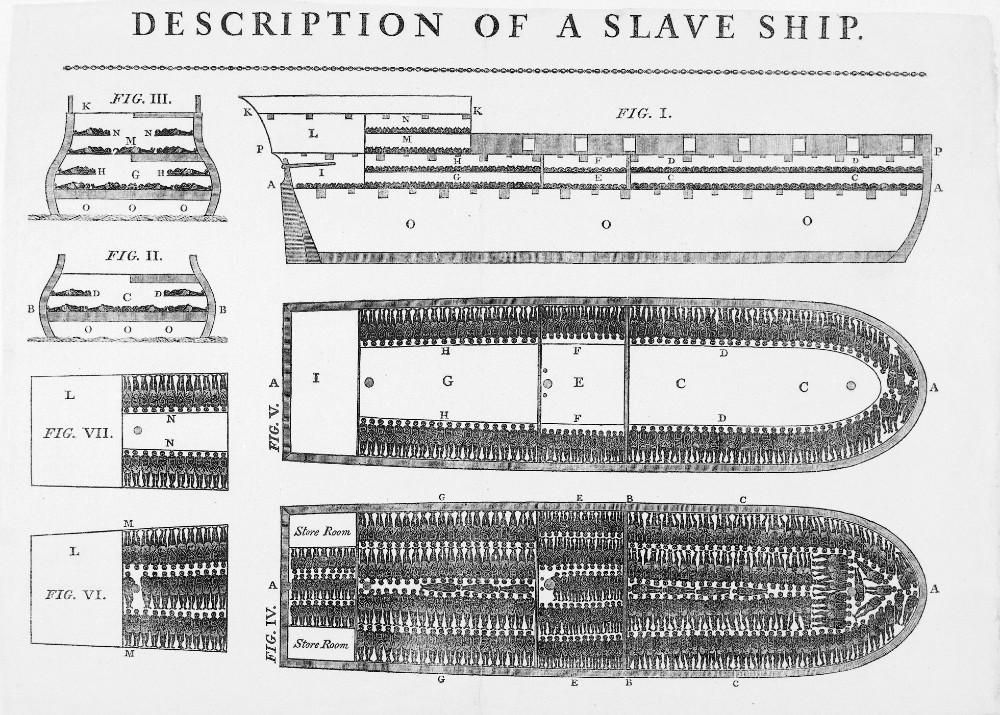

I have always felt lucky because I grew up in Jamaica just as it became independent. We turned to our history to create a collective national identity. We named national heroes that led rebellions against slavery and led us towards independence. We used text books that told us that the Africans transported to the Caribbean came from particular tribes. We recited their names like poetry: Ashanti, Fanti, Ebo, Coromantee. We researched and celebrated the literature, visual art, music and dance created by our turbulent history, one that included indigenous people, European invaders, enslaved and indentured peoples from Africa and India, traders and businessfolk from the Middle East, China and the Portuguese Jewish community. I came to live in the UK possessing this history.

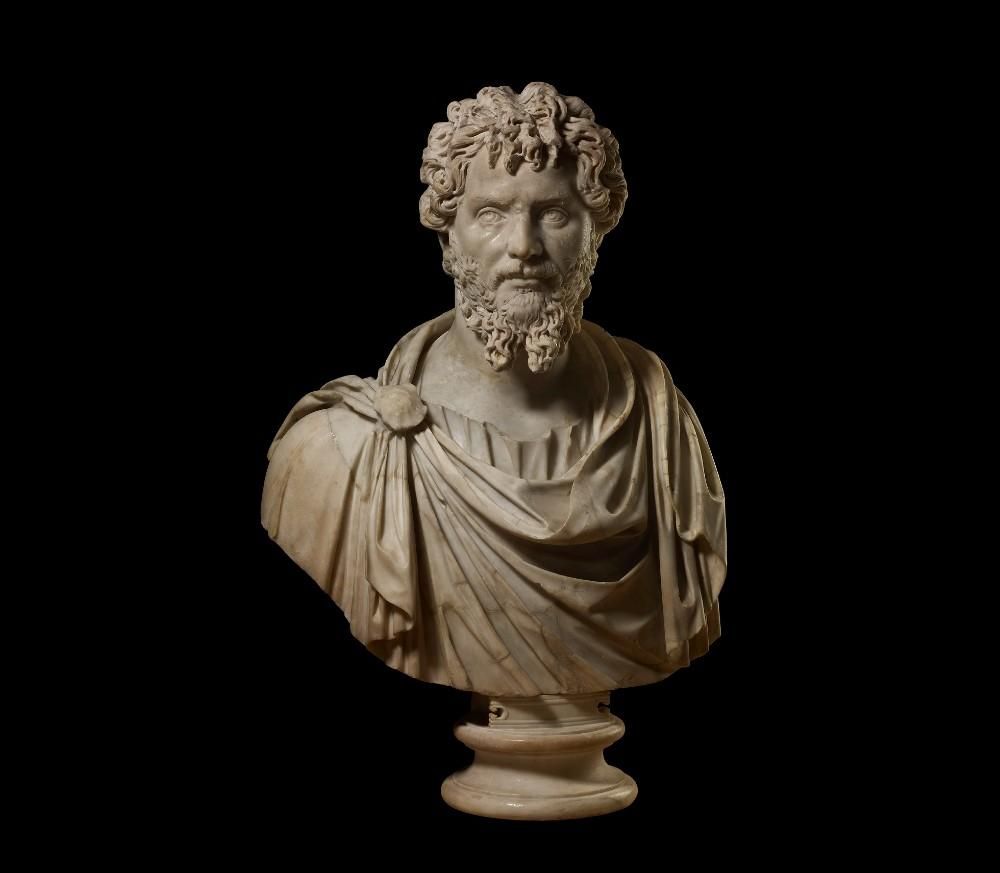

Black History Month in the UK came to mean two things for me: being asked to speak to young people about Caribbean history (and being surprised how little they knew) and always finding out some new and wonderful fact I did not know about the history of Black people in Britain. The story of John Simmonds, the slave press ganged into the British Navy who fought under Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar for example, the tragic Ethiopian prince fostered by Queen Victoria, or Septimius Severus, the Roman general. (All of this and more has been brilliantly brought together by David Olusoga in his book Black and British: A Forgotten History.) It is, after all, common sense that the histories of Africa and Europe should be closely intertwined. They are part of the contiguous landmass of Europe, Asia and Africa.

Museums have always fascinated me. I studied Archaeology and Anthropology at university and know how much is learnt from the close study of the objects humans create. In the past, I would conscientiously read the labels on displays. Nowadays I spend more time considering the objects themselves, looking for a different, more direct connection.

I have held a handaxe from Olduvai in Tanzania in my hand and known that it was made over a million years ago. I've seen the beauty of hand-painted sarcophagi from Egypt and Sudan, and admired the brilliant craftsmanship of the ivory mask and brass heads from Benin.

The passion and pain that created the modern artwork Throne of Weapons by Kester Canhavato always reminds me in the most visceral way of the struggle of Black people to create, from an often dark and painful history, objects of beauty that celebrate our survival and the wisdom we've gathered.

At a time when racist and fascist movements have resurfaced in the west and new centres of political and economic power are emerging, events like Black History Month encourage enlightenment for all. Everyone should hear themselves represented in the national conversation so no one retreats to their own social or digital xenophobic echo chamber. Our histories are glorious and painful and intertwined and surprising. Now more than ever, we need to understand them all.