View some of these objects at the special exhibition Legion: life in the Roman army exhibition (1 February 2024 – 23 June 2024)

'Behind every great man there stands a woman', or so the saying goes.

It's a phrase that acknowledges how women are often eclipsed from a history of men's achievements. Legion may be an exhibition about the Roman army, but proves that women were there too – if not on the battlefield, then in the fort. For better or worse, women were part of the imperial machine. Men may have done the fighting, but a picture of Roman military life without women is just wrong, says Mary Beard.

Marble portrait

The Roman empress Julia Domna was a force to be reckoned with. Born in Syria in around AD 160, the wife of the emperor Septimius Severus (reigned AD 193–211), and mother of his heirs, the emperors Caracalla and Geta, she does not now have the popular fame of some of her predecessors. She doesn't, for example, have the name recognition of the scheming, power-hungry Livia, wife of the first emperor Augustus (31 BC – AD 14). Unlike Livia, who was so memorably recreated by Robert Graves in I, Claudius (and later even more memorably by Sian Phillips in the BBC television adaptation of the novel), Julia Domna has not been much of a star in film or fiction. She tends to lurk in specialist textbooks. But Legion: life in the Roman army (open until 23 June) brings her back into the limelight.

There is a stunning marble portrait of her in the show – next to one of her husband (they half look at each other) – wearing a curly layered wig, with wisps of her own hair creeping out from beneath it. Marble busts are how we usually know the faces of Roman rulers and their families, but portrait painting was also a major art form in the ancient world. In fact, marble sculptures were probably originally outnumbered by paintings, hanging in temples, council offices, bars or private houses. Few of these painted portraits now survive, whether of the imperial family or of more ordinary folk. But when they do – and the portraits inserted into Egyptian mummies of the Roman period are the best known and best preserved examples – they bring to vivid technicolour life the faces of those we otherwise know from white marble.

The bust in Legion shows Julia Domna's polished, public persona. But one extremely rare painting on wood from Roman Egypt (now in Berlin) takes us beyond that directly into a royal family drama. In the painting, the empress and emperor stare out at us, regally, much as they do in the marble busts: he sporting a golden diadem (a crown in the style of a headband) inset with jewels; she in that layered wig again. In front of them are Caracalla and Geta – or at least they originally were in front of them. After the death of Septimius Severus, this pair briefly ruled together, until Caracalla eliminated Geta in order to rule alone. Geta's face was eliminated from this portrait too, leaving just an ugly splodge. The murder is said to have been carried out while the young man clung to Julia Domna's lap. In one of the most poignant (or bathetic) moments in Roman history, his last words, as reported, were 'Mummy, mummy, I'm being killed'.

Domna

But Julia Domna was more than a 'mummy'. During Septimius Severus' reign, she acted as a power broker, receiving embassies and putting in a good word for them with her husband (in gratitude the people of Athens honoured her as the 'saviour of their city' and celebrated her birthday each year). She was a keen philosopher, who exchanged learned letters with leading (male) intellectuals of the day, even being said to have sponsored her own philosophical circle (or research group, as we might say). She was nicknamed 'Julia Domna the wise', a rare compliment for a woman in ancient times. And, as Legion shows, she had a striking military presence too. She went with her husband on campaign and one of her imperial titles was 'Mother of the Army Camps' (mater castrorum in Latin).

Agrippina

In this respect, she was like some earlier imperial ladies. In the first century AD, for example, Agrippina, the mother of the emperor Caligula and a rough contemporary of Livia, went on expeditions with her husband. On one critical occasion in Germany, she is supposed to have single-handedly stopped Roman soldiers from deserting their posts, and, on another, she is said to have visited the wounded in the ancient equivalent of a field hospital. She even took her young son with her and dressed him up in a miniature soldier's uniform complete with army boots (so giving him his familiar name: 'Caligula' means 'little boots' or 'bootikins'). Needless to say, some Roman critics were not impressed by any of this: it was a woman taking over the role of a man.

Women's roles

How true were these stories? How typical of a woman's role? And what do they tell us more generally about women and the Roman military machine? It would be utterly wrong to think that women in Rome were ever army leaders, or that empresses ever got very close to the fighting (I don't imagine they often slept under canvas or – if they did – only in very glamorous tents). No women ever officially served in the Roman army. The critics of Agrippina were probably typical of most Romans in thinking that war was men's business. Even the honorific title 'Mother of the Army Camps' makes it clear that Julia Domna's role was to be seen as maternal as much as commanding.

Violent history

The unsurprising truth is that women in general were far more often the victims of ancient warfare than active participants. The long, sad history of the rape of the defeated goes back to the Romans and earlier. The scenes of Roman reprisals against the Germans, sculpted on the column in Rome erected to commemorate the military successes of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, include several scenes of women being (to put it euphemistically) 'carried off'. Closer to home, I suspect that not many people know that the first surviving representation of 'Britannia' in art (a sculptured marble panel from the mid-first century AD, from the Roman city of Aphrodisias in modern Turkey) shows her not as the stately, powerful warrior as we now see her, but as the semi-naked, sexual victim of the emperor Claudius, who conquered the province in AD 43.

Married quarters

All the same, Legion does reveal the world of the Roman army to be, at every level, much less exclusively male than we often imagine it to be. One message that I took away from the exhibition was a simple one: if we don't put women back into our picture of Roman military life, we haven't pictured it right. Roman army camps were not 'men-only' zones. Right down to the ordinary squaddie, who couldn't officially get married, Roman soldiers had partners and children who lived with them on, or near, their bases. In fact, one of the soldiers featured in Legion even wrote home, in a letter on papyrus that still survives, to announce proudly that he now has an (unofficial) wife and son. I remember being taught as a student that the civilian settlements that often grew up around Roman forts were for 'camp followers', implying hucksters and sex workers, considered a generally disreputable crowd. I now see that they were just as likely to have been centres for domestic family life: in our terms, these were the married quarters.

Vindolanda

There is plenty of clear archaeological evidence too for the presence of women and families in these Roman military contexts. Excavation of the drains of the bath building in one fort on Hadrian's Wall have produced objects, such as hairpins and children's first teeth, lost in the bath and swept into the drain, that make it absolutely certain that the clientèle included women and families. And the leather shoes found at Vindolanda, an army base just south of Hadrian's Wall, prove that there were women and children on the base (unless the soldiers in residence had implausibly small and delicate feet).

Vindolanda

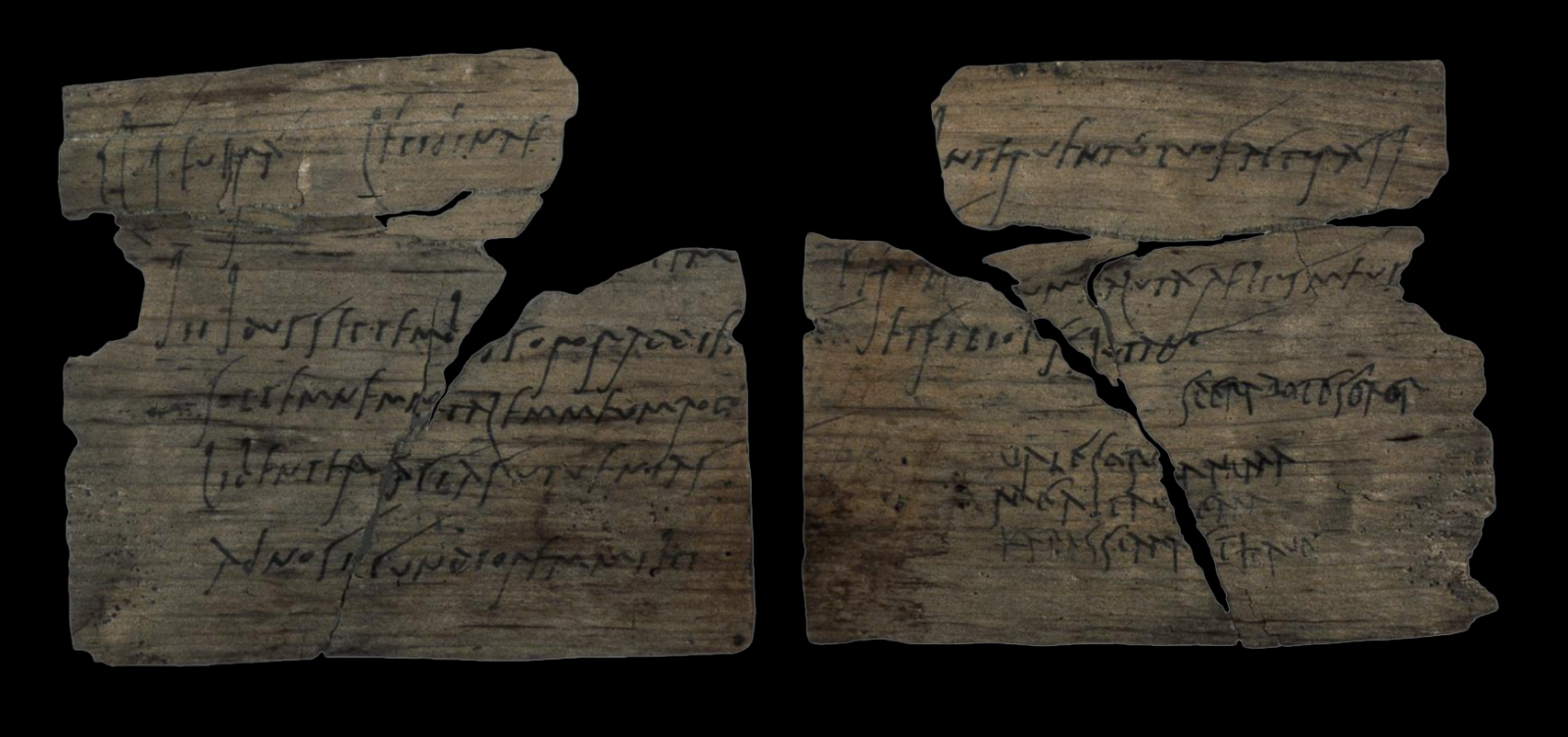

Vindolanda is also the place where we find actual written evidence for the presence of women, more upmarket ones, but well below the rank of the imperial family. The officer class in the Roman army were allowed to marry, and their wives and families regularly went with them on their postings. The documents discovered in the waterlogged conditions at Vindolanda (both extreme wet and extreme dry preserve this kind of material) give a glimpse of what women's life was like on these bases. The most appealing, and now famous, of all is the letter sent to Lepidina, the commander's wife at Vindolanda, from a female friend at a nearby camp, Claudia Severa, inviting her to a birthday party. (Most of the letter is written by a secretary, but Claudia Severa's own 'sign off' is the earliest writing definitely by a woman known from Britain.) Other letters preserved at Vindolanda show Lepidina acting, at a lower social level, rather like Julia Domna, doing favours and supporting her friends, associates and dependants. One woman explains, for example, in a letter to Lepidina's husband, that she has already approached Lepidina for help with her problem (whatever that problem was, we do not know). In the world of these far-flung northern army camps, it seems that one person who might help you out in your difficulties was the commander's wife.

Regina

But my favourite woman on Hadrian's Wall, almost certainly connected to the army in some way, is another star of the Legion show: Regina. Regina's tombstone, from the second century AD, was discovered in South Shields some 150 years ago. It contains few words, but they tell us loud and clear that: Regina was the much-loved wife of a man named Barates, who was himself, like Julia Domna, a Syrian, from the town of Palmyra; that Regina had come from the south of England, from near St Albans; and that she had been the slave of her husband until they married and he freed her. At the bottom of the stone, which is mostly taken up with a sculpted image of Regina, sitting with her wool working equipment and jewel box, are a few words in Barates' native Aramaic, lamenting the loss of his wife. We do not know for certain that Barates was attached to the army. He could have been a trader of some kind. But if another, fragmentary, tombstone found not far away, commemorating a man 'from Palmyra' whose name ended with the letters '...rathes', was the memorial to the same 'Barates', then he seems to have been a military standard bearer.

Regina and Barates are usually treated as an example of the multi-culturalism of Roman Britain. Here, in second-century AD South Shields, we have the Syrian immigrant marrying the local British girl. They are also an example of the complexity of slavery. Barates marries his ex-slave – was this a union of love or of exploitation (or both)? Whatever the nature of their connection, they are very likely also a great example of the way that women were always there, through choice or otherwise, with the Roman army. The Legion exhibition helps bring back into the limelight women, from empress to ex-slave, whom we have too long overlooked.