See the exhibition

Burma to Myanmar is open from 2 November 2023 – 11 February 2024.

Journey through time at the crossroads of Southeast Asia.

The history of Myanmar – also known as Burma – is a complex web of faith, culture, trade and empire and this timeline helps you navigate through the millennia. Explore the rich plurality of the kingdoms, empires, trading hubs, kinship networks and states that once composed Myanmar; their colonisation by the British; and the events since independence in 1948.

Burma to Myanmar timeline

200 BC – about AD 900

Early peoples in present-day Myanmar

About AD 800–1300

Buddhist networks

About 1100–1500

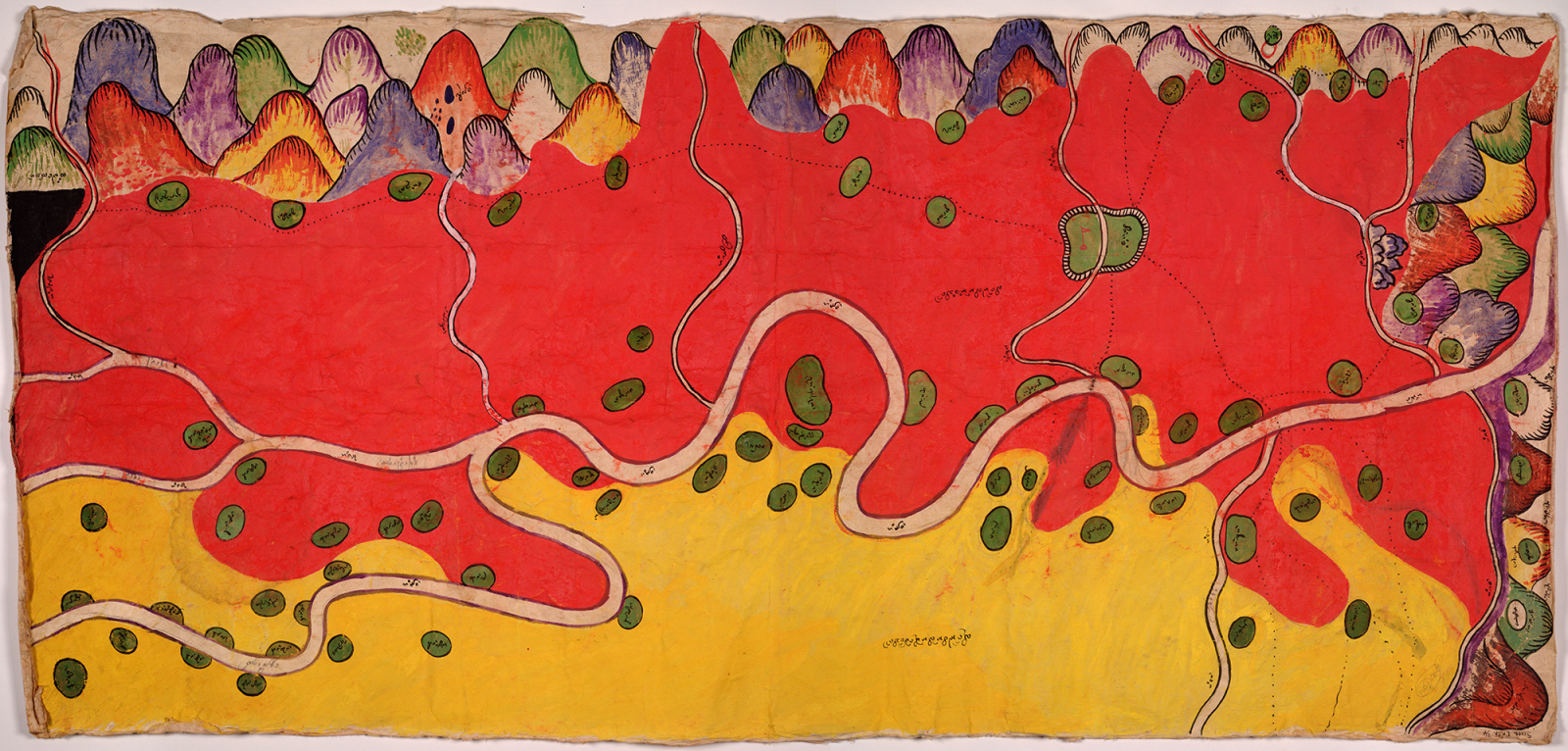

Trading connections

1500s–1600s

Flourishing kingdoms

1550s–1820s

Expanding empires

1800s–1930s

Highland regions

Until the 1880s

Spheres of influence

1826–1948

Colonial eclipse

About 1863

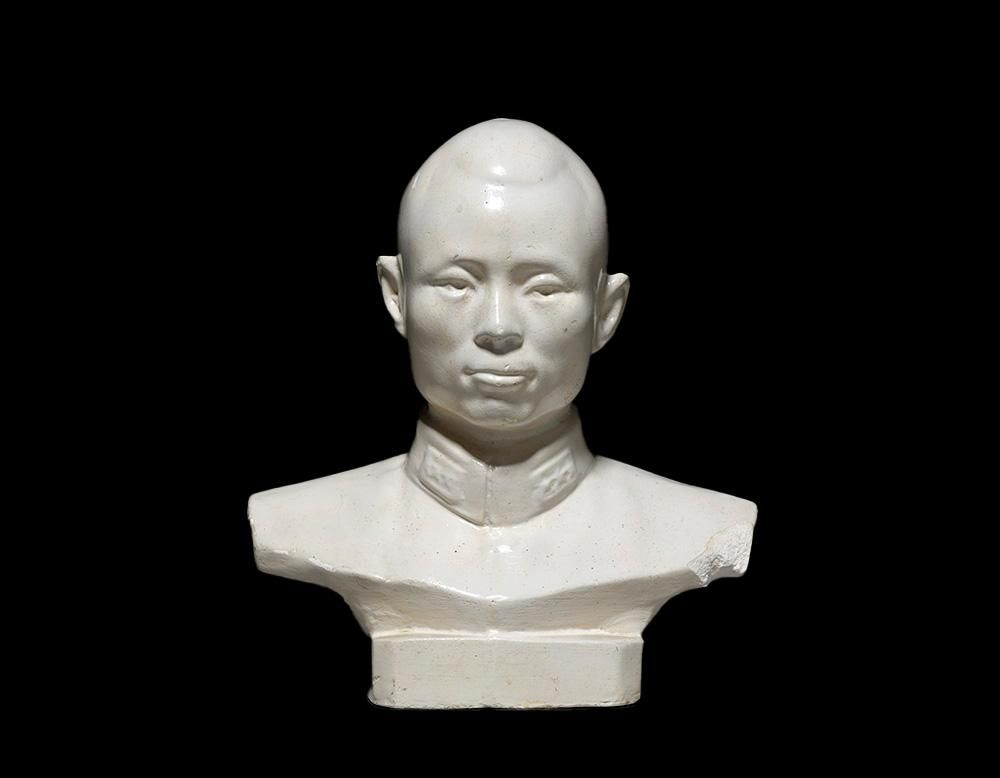

New materials

1870s–1948

Ethnicities

1940s

The Second World War

Since 1948

After independence