The Museum's objects from Egypt span from prehistory to the present. In 2016 the modern Egypt project was launched to bring the collection into the 21st century. Objects from housewares and everyday items to ephemera and photographs can tell stories about historical, economic and cultural developments in Egypt over the past century.

Collecting modern Egypt

Cairo's Friday market is a bustling and sprawling affair stretching for several kilometres, bordered on one side by an elevated highway and on the other by the City of the Dead, one of Cairo's oldest and largest cemeteries. There, I found a minty green sewing machine, collecting mud and dirt as it sat on the pavement along the road, waiting for buyers. The machine tells a rich and complex story about Egypt's modernity and transformation during the middle decades of the 20th century. The Museum's modern Egypt project is helping to recover such stories and histories which otherwise would be neglected and remain untold, particularly within the context of museums.

The Nefertiti sewing machine was manufactured in the 1950s and 60s in Egypt by the country's military factories. Following the 1952 coup d'état, the factories expanded their scope of work in the early 50s to include household items. Within the framework of nationalist modernisation politics and the desire to increase national production, the machine was created to provide jobless women with a means for improving their income. The sleek design, the colour choice and the iconography of Nefertiti were all meant to appeal to a wide demographic of aspiring Egyptians seeking class mobility and modern lifestyles. Reference to ancient Egyptian icons and figures in the naming of modern machinery was common during the period. For example, an Egyptian-manufactured car, produced between 1960 and 1972, was named Ramsis. The Nefertiti sewing machine became ubiquitous, yet it was not as successful as its makers intended. Today, the machine is a reminder of a top-down modernising project by the state in postcolonial Egypt.

A notable feature of the Nefertiti machine is the hand-painted calligraphy. The development of Arabic calligraphy in 20th-century Egypt is tremendously significant, yet rarely studied. What happened to Arabic script in the Middle East's most populous country as modernity introduced new objects into everyday life? How did local and international products designed for mass consumption utilise the script on objects and in advertising? And how did the state confront the problem of illiteracy during this time? With the project, we hope to start to answer some of these questions.

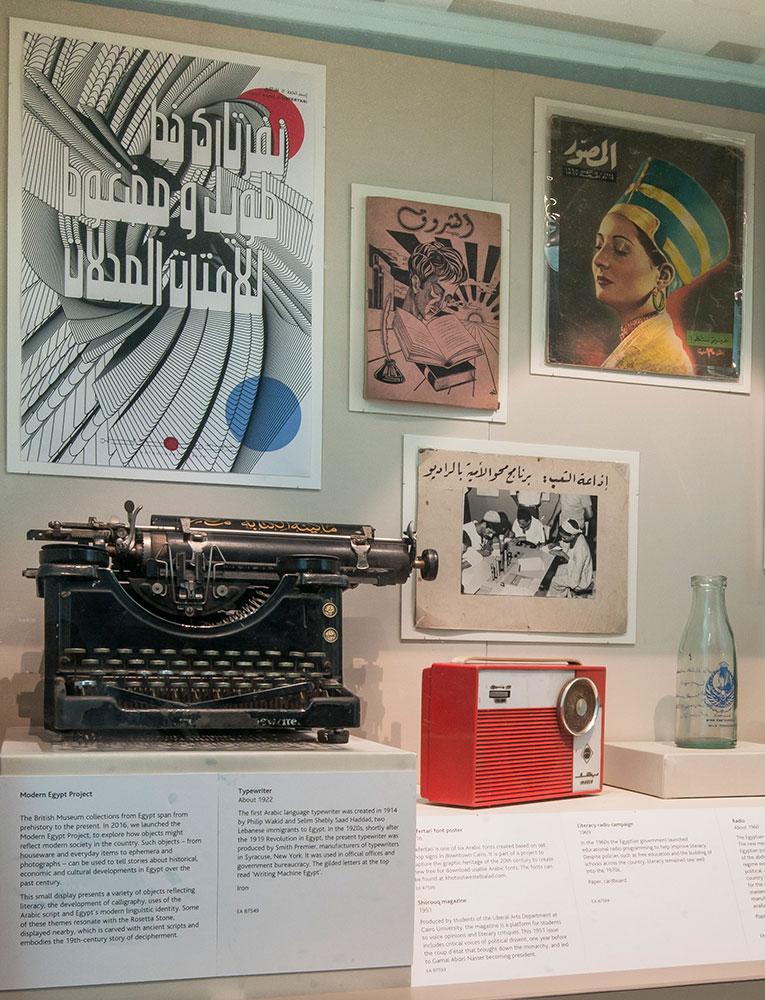

A small display of ten objects acquired in the first months of the project is now on view in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery (Room 4), next to the Rosetta Stone. The objects – including periodicals, photography, one of the oldest Arabic language typewriters, and an ornate personalised picture frame – all provide snapshots into the history of writing, typographic development and literacy in 20th-century Egypt. Some of these themes resonate with the Rosetta Stone itself – its carved ancient scripts embody the 19th-century story of decipherment.

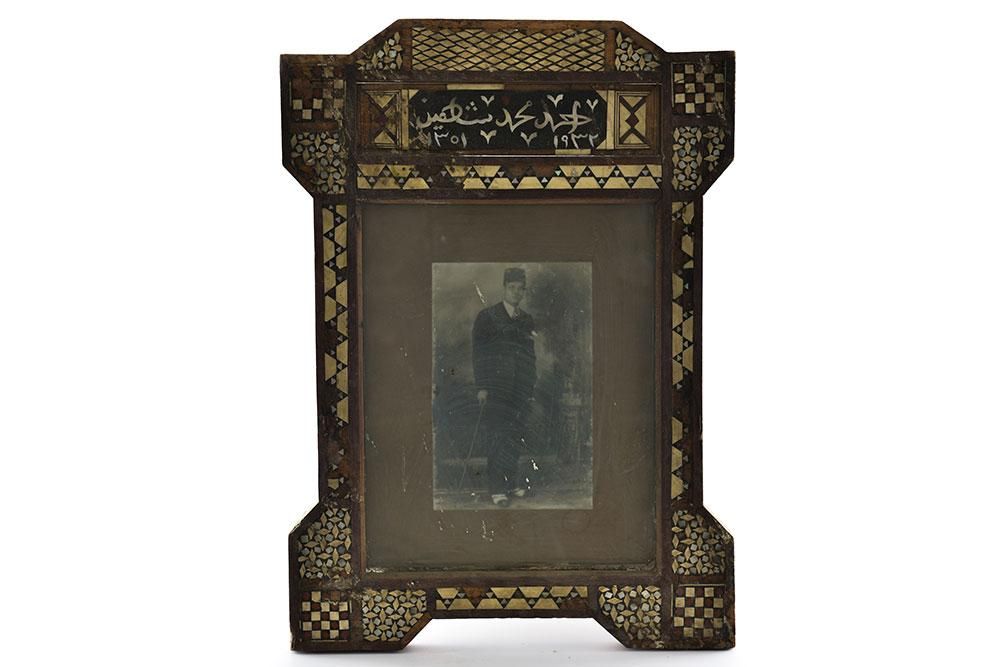

The objects on display illustrate how the project can expand the Museum's collection to include recent artefacts that tell stories about the modern and contemporary worlds. One of the objects in the display is a framed portrait of a man whose name and the date of the photograph (1932) are inscribed with seashells within an elaborate wooden frame, referencing the rich history of Islamic architecture and design in Egypt. The pictured man is an efendi, a new social category of men that emerged in the beginning of the 20th century. The efendiyya, as a social group, emerged from the expansion of education and the increased awareness of national identity and Egyptian conceptions of modernity. They were bureaucrats, teachers and accountants.

In this particular object, we see a personification of this 'new' Egyptian man, dressed in the suit and fez. He is an embodiment of a balancing act between Egyptian modernity and authenticity. The custom-made inlaid frame bears the name of the efendi pictured, 'Ahmed Mohamed Chahine.' Studio photography was already widely popular by the early 20th century. The intricately designed frame with art deco and arabesque elements adds to the overall self-representation of the efendi as a modern subject. This object shows us the impact of increased education to combat illiteracy in Egypt, the production of a new type of Egyptian, and the efforts to utilise Arabic script to personalise and mark the modern identity of this figure.

Throughout the 20th century the Egyptian state made efforts to expand education and combat illiteracy. Two objects in the current display shed light on a chapter of this history. A red-and-white transistor radio, manufactured in Egypt in the 1950s, was part of the state's attempts to make this technology available to a wider audience. The radio was instrumental not only for the dissemination of news and information, as well as propaganda, but it also allowed for educational programming to combat illiteracy. A mounted photograph dated 1969 depicts this close relationship between radio and literacy programming by the government at the time.

The project is an exciting initiative to expand the ways in which the modern world is collected and displayed, particularly in a location such as the British Museum, which has long been associated with the rich ancient history of Egypt. The current small display shows some of the types of objects that can tell rich and complex stories seldom presented in the context of museums – not only in the UK, but also around the world.

Find out more about the Department of Egypt and Sudan.