View these works by Michelangelo at the special exhibition Michelangelo: the last decades (2 May 2024 – 28 July 2024).

In 1534, Michelangelo Buonarroti was 59 years old and already the most celebrated artist in Europe.

He had mastered the fields of sculpture, painting and architecture, and was a gifted amateur poet. Now, as he moved from his native Florence back to Rome – where Pope Clement VII had commissioned him to paint the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel – he would have been justified in assuming that he was beginning to wind down his long and varied career. But, as exhibition curator Sarah Vowles explores, it marked an exciting new beginning…

Intro

In the 16th century, 60 was a very respectable age to live to – and Michelangelo can hardly have expected to live for a further 30 years after returning to Rome. But in the last three decades of his life, until his death at the age of almost 89, he was busier than he had ever been, as successive popes drew on his expertise and imagination to commission a series of increasingly demanding projects. It is this late and unexpectedly energetic period that forms the focus of our exhibition Michelangelo: the last decades (2 May – 28 July 2024).

The return to Rome

First, there was the Last Judgment, painted on the wall directly beneath the superb Sistine Chapel ceiling that had helped to make Michelangelo's name in his thirties. As a fresco, this had to be painted onto wet plaster, a careful day-by-day process that required a great deal of advance planning, and which resulted in a series of wonderful preparatory drawings, ranging from dynamic compositional designs from early in the process, to refined final studies of heads and figures.

But this wasn't the end of the pope's ambitions for Michelangelo. Next, there were two further frescoes in the neighbouring Pauline Chapel, the pope's private place of prayer. And then there was the greatest and most challenging project of them all: supervision of the building site at St Peter's, where the church at the very centre of the Catholic world was rising, phoenix-like, from the rubble of the ancient basilica. At one point in the 1540s, venting his frustrations on the back of a study for the Pauline Chapel, Michelangelo had grumbled, 'I'm not an architect,' but his patrons weren't listening: in the final 20 years of his life, he was involved in projects for the Palazzo Farnese, the Porta Pia and the Piazza del Campidoglio, not to mention St Peter's iconic dome, ultimately stamping his vision upon the very fabric of Renaissance Rome.

New collaborations

Michelangelo had always preferred to work alone but now, as he struggled with ill health and the physical challenges of old age, he had to learn to adapt. He formalised a system which he'd occasionally used in his younger days, working in collaboration with a specialist panel painter in order to satisfy demand from non-papal patrons. Michelangelo would create a composition which the painter – usually Marcello Venusti, his chief collaborator – then translated onto panel, adding a setting and other details from his own imagination. For example, Michelangelo's designs for The Purification of the Temple, conceiving the figures in the shape of a lunette (a crescent), were adapted by Venusti in an upright painting which placed them among dramatic Solomonic columns (with a twisting shaft), intended to evoke not only the Temple in Jerusalem, but also St Peter's itself. The collaborative system was immensely successful: it allowed patrons to own a piece of art conceived by the perennially overworked Michelangelo, executed by a colleague with the master's authority and approval.

Although Venusti seems to have been Michelangelo's preferred partner, he did also design or give his compositions to other artists: most notably, the towering cartoon (a full-scale preparatory drawing) of the Epifania, which seems to have been left in Michelangelo's workshop after the related commission fell through. This huge drawing, over two metres tall and almost two metres wide, was granted to Michelangelo's associate Ascanio Condivi, probably in thanks for the flattering biography that Condivi wrote of him in 1553. Condivi himself was at the start of his artistic career and needed a big break; to be given a design by Michelangelo was a huge honour.

Condivi's painting of the Epifania is now in the collection of Casa Buonarroti in Florence, the museum set up in Michelangelo's family home, and has been conserved especially for the exhibition, with support from the British Museum. In the exhibition, it will be reunited with Michelangelo's drawing of the subject – also newly conserved for the occasion – for the first time since the 16th century.

Private passions

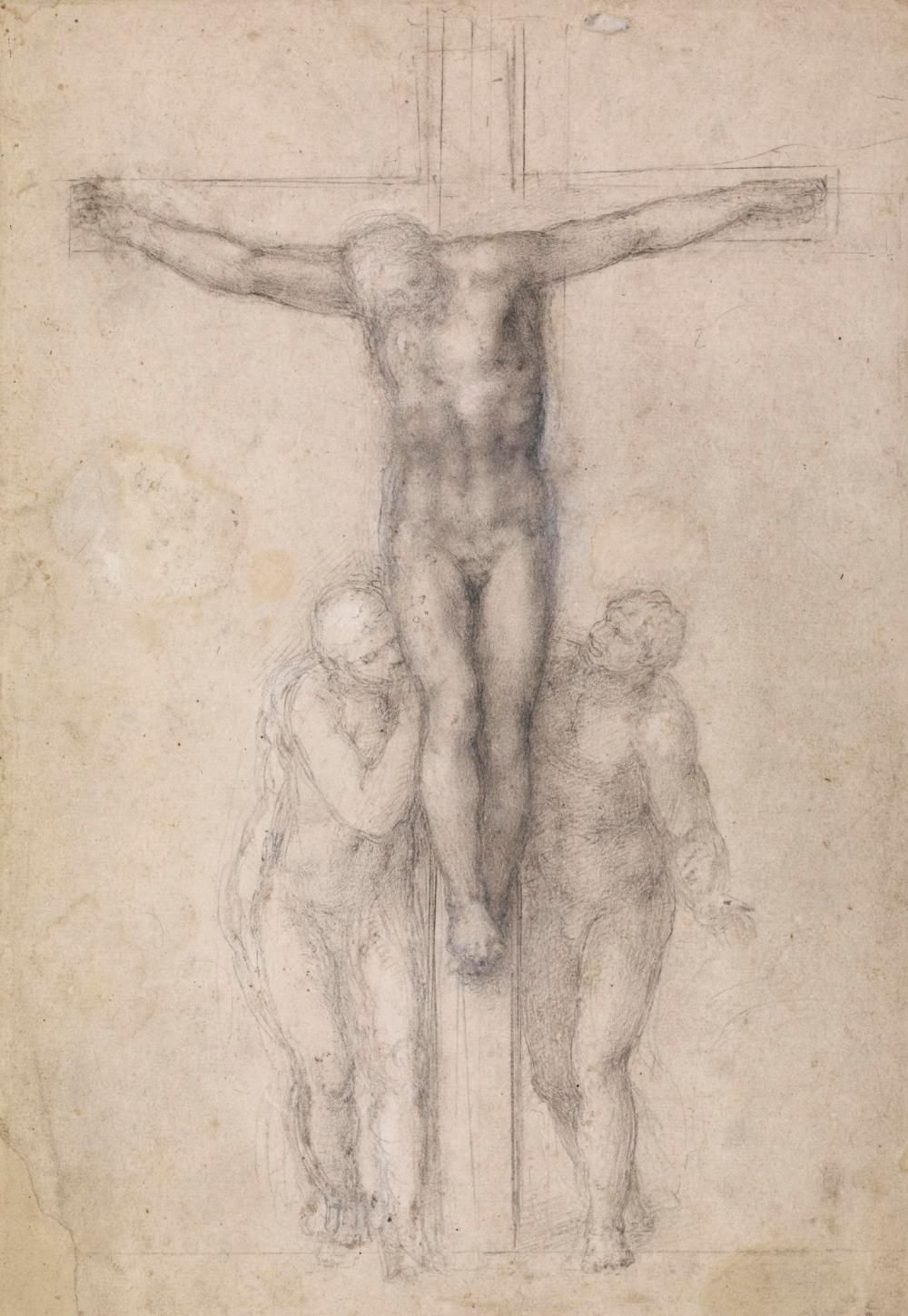

The British Museum exhibition, however, looks beyond Michelangelo the artist and tries to offer visitors a better impression of the man himself. Michelangelo certainly could be gruff and prickly, easily sparked to annoyance, as we see in the lively letters he wrote to his long-suffering nephew Leonardo. But he was also capable of great affection and warmth, and the show considers two of his most significant relationships during this late period, with the young Roman nobleman Tommaso de' Cavalieri and the aristocratic poet Vittoria Colonna. Both friendships prompted the creation of poems and refined artistic designs which drew on shared interests: for Tommaso, exquisite mythological allegories, such as the Fall of Phaeton, which offered moral guidance to the young man; and, for Vittoria, religious iconography such as Christ on the Cross, which drew on the intensely intimate imagery of reforming movements, evoking the tragedy and triumph of Christ's death, and his redemption of humankind.

Drawing on faith

Michelangelo was a devout Catholic and, as he grew older, was increasingly worried about the state of his soul. He sent large sums of money to Florence, via his nephew Leonardo, so that it could be used for charitable purposes, and both his art and his poetry show a profound and intimate engagement with questions of salvation. The intensity of his concern becomes even more understandable when we consider the times in which he lived: Rome was still reeling from the impact of the Reformation in Northern Europe (which challenged many aspects of traditional Catholic doctrine) and the Catholic church was trying to define its response. One of the most moving examples of Michelangelo's personal exploration of faith is a group of drawings of the Crucifixion, probably made over an extended period of time during the last 10 years of his life, which show the elderly artist turning to the act of drawing as a means of spiritual meditation – using variations on a single theme to explore his feelings about mortality, sacrifice, faith and the prospect of redemption.

Conclusion

The popular perception of Michelangelo focuses on the famous works of his youth: the David, for example, or the Sistine Chapel ceiling. What we hope to do in this exhibition is to introduce people to the remarkable variety and inventiveness of his career between the ages of 59 and 89, celebrating his continued creativity and determination in the face of the universal challenges of old age. By bringing out Michelangelo's own voice, from letters, poetry and other documents, and by considering his friendships and his own very human doubts and vulnerabilities, we hope that visitors will have the chance to appreciate both the works and the man in a different, more intimate light.

Michelangelo: the last decades opens 2 May. Book your ticket now to save at least 20% on the standard price with our early bird offer.

Supported by

James Bartos, Dunard Fund and a gift in memory of Melvin R. Seiden