View the relief at the special exhibition Legion: life in the Roman army exhibition (1 February 2024 – 23 June 2024)

Conservator Kathryn Oliver reveals how high-tech lasers can put us in direct touch with Roman makers' marks – and uncover the glorious detail of the turning point in a battle.

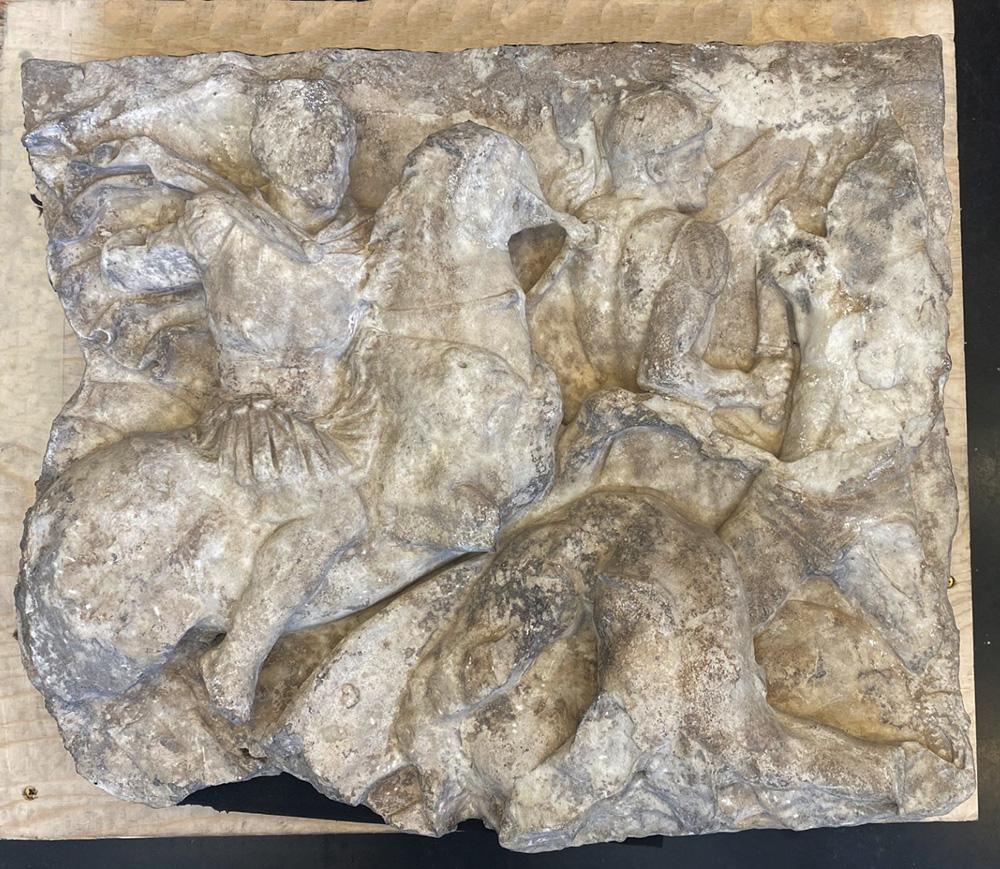

A Roman relief

In the burial practices of ancient Rome, marble and limestone sarcophagi were often elaborately carved in relief with scenes that depicted the deceased's occupation or important battles they may have fought in. Legion: life in the Roman army focuses on the experiences of ordinary soldiers and their families, and these objects allow us to piece together and tell these stories. The marble relief pictured at the top of the page – and on display in Legion – is a fragment of a larger, unknown carving believed to be part of a sarcophagus. We can clearly see a Roman soldier riding into battle, trampling a barbarian who lies over the neck of his horse on the ground. A second soldier is riding off to the right, wearing a helmet and raising his sword to another barbarian, whose face and body are now missing. The relief depicts the last stages of a successful battle and perhaps a moment of glory for the deceased: the cavalry is brought in once the enemy's ranks have been broken to scatter them into retreat.

The relief arrived in the Stone Wall Paintings and Mosaics Conservation Studio, where our aim was to clean it and prepare it for display in Legion: life in the Roman army.

History of the relief

Donated in 1951 by Mrs Ivor Griffiths, it is believed to have been previously in the collection of Gordon McNeill Rushforth, an established scholar who taught ancient Roman history at the University of Oxford and had a passion for art and sculpture. We are not certain of its origins beyond this point. It was on display at the British Museum for many years until the gallery it was in closed to the public in the 1990s. It has remained in storage ever since. This is the first time in 30 years that conservators have been able to examine the relief and bring the story it tells back to life.

Mortar and render

First, our team studied the relief. Its condition had changed very little from when it arrived at the Museum. We could see that the carving was obscured by surface-level dirt, but also by the remains of mortar and render. The presence of these materials suggested that, at some point between excavation and its donation to the Museum, the relief had been built into a wall. All four sides of the fragment have broken edges and there were extensive mortar and render remains over the surface and over these breaks in particular. Gypsum plaster traces around the break edges also suggested that attempts had been made to replicate the missing features, such as the heads of the soldiers and the horses. In some places the mortar was layered over the top of plaster remains, which helped us understand how the original restorers might have gone about it: first they restored the relief with plaster, then used mortar to build it into a wall. The traces of these materials were very distracting to the eye and masked the carving from the viewer, so it was important to remove it all.

Conservation challenge

I expected the mortar to soften with water and to be able to remove it with small hand tools, however I soon found this to be problematic. The mortar was covering some areas where the stone was laminating (cracked, with thin layers of the stone separating from the rest) or sugary (where the stone becomes powdery and grains can easily be dislodged from the surface) which would be easily compromised if the mortar was removed with hand tools. A different system had to be found.

Laser cleaning

In the past the stone had been cleaned using deionised water and a cotton swab, leaving the mortar behind, but today we have a different tool available to us. After dusting the relief using a soft brush and vacuum, I carried out further cleaning trials – using lasers. At the British Museum, we have two lasers which work at three different wavelengths to remove different kinds of matter in a variety of ways. I experimented and found that the Q-switched ND YAG dual-wavelength laser set at a near–infrared wavelength of 1064nm (nanometres) worked well, especially when the surface was wetted first.

Laser cleaning can be used in several ways but is commonly used to remove dark matter from a light background. This is because the light energy is more easily absorbed by the dark material than the lighter stone behind. So, at the right level, the mortar absorbed the light, exciting the molecules and breaking them away from the surface in a process called 'ablation', without affecting the lighter marble at all. This can be slow work though, especially where the mortar is thick and hard. So, I started by softening the mortar in these areas with deionised water and removing the top layers with a scalpel, then gently removed the last thin layers with the laser.

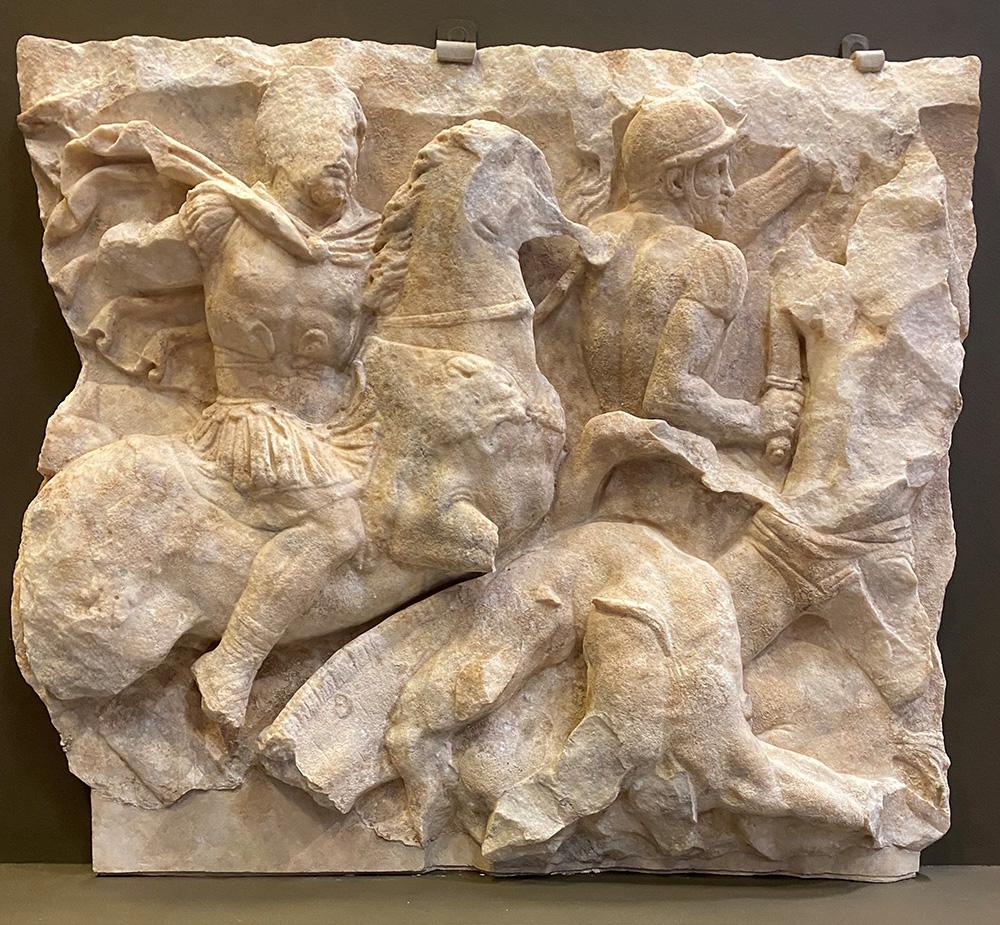

Original Roman makers' marks

As I removed more and more of the mortar, I could see the original carving and the condition of the stone much better. I was then able to remove residues from around areas of stone that were particularly fragile without any damage to them. Once clean, I could consolidate these areas by applying a dilute adhesive into the cracks using a syringe or paintbrush. Incredibly, beneath the mortar and render, I uncovered original tool marks beneath the curvature of the horse that we were previously unaware of. These tool marks were likely made using a riffler, a tool like a file used to help shape stone before the final smoothing stages. These kinds of marks can still be seen on some sculptures in sheltered areas which have been left slightly unfinished and are less exposed to erosion, but I had not expected to find them on this sculpture as it was so eroded on some of the more exposed surfaces.

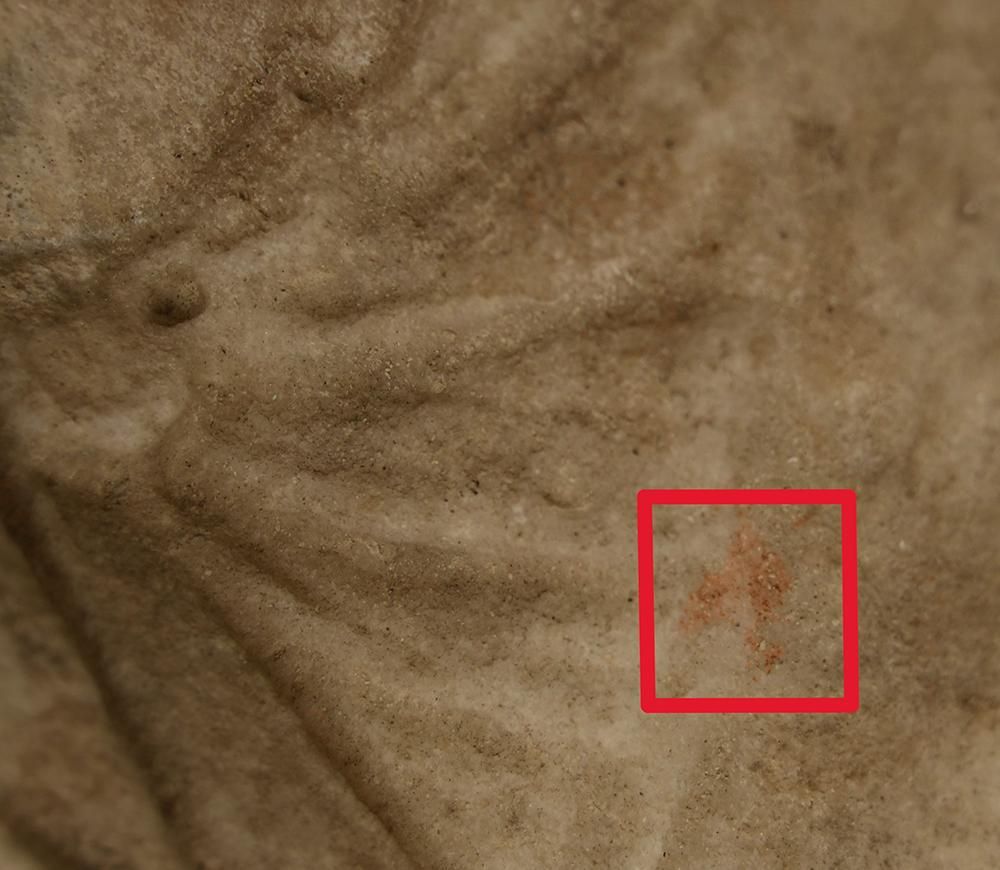

Red Roman pigment

In other sheltered areas I discovered the remains of some red pigment. Most Roman sculptures were painted in bright, vibrant colours to reflect real life. At this stage we have not confirmed if this red is an original pigment such as hematite (an iron-oxide compound), but it is an exciting possibility.

Sarcophagus or architecture?

Some of the details we uncovered left Thorsten Opper, Curator of Roman Collections and I wondering about the true original use of this relief. Marble reliefs like this are often found on sarcophagi, but without any known records about its origin beyond the collection of McNeill Rushforth, we have nothing fixed to confirm that it actually was. The back wall of the relief is about 30–40mm thick, but the walls of sarcophagi are usually considerably thicker (usually about 100 mm). One possibility is that the thicker back surface was cut after excavation to make it lighter – but chisel marks and surface dirt, and a lack of mortar remains, makes it consistent with the interior of a stone sarcophagus. There are no saw marks, as there would be if the stone had been later cut through. Another possibility is that the fragment is not from a sarcophagus, but was once part of a smaller relief, perhaps of architectural use. Without this conservation work we may not have questioned the relief's original setting. Considering alternatives might subtly shift our understanding of the purpose of the carving and the meaning of the scene it depicts.

Test of time

When treating an object, we always consider the future of the work we carry out. Conservators aim to use materials which will not change with time: we don't want them to change colour or break down, but they do need to be removable if necessary, in the future, without risking damage to the stone. To consolidate the cracks in this object I used an adhesive which had been tested to ensure it would not change colour. The adhesive can add strength even in low quantities. We diluted it in solvents so that it could flow deeper into the gaps, but we were also able to use it in higher concentrations and mix it with other materials to make a filler to support the fissures. The fills were bright white so I painted them to match the surrounding stone, again using paints which could be removed with a little solvent without affecting the stone.

Supporting the object

Our final concern was with the stability of the object. The broken edge along the bottom was not flat, which meant that the object could not stand vertically on its own. The removal of the mortar had also exposed a lot of thin stone along this bottom edge, with sharp points that could be damaged if too much weight was put on them. To help support the relief and hold it at the correct angle, I built up the bottom edge using a combination of materials. The first layer was a barrier layer about 5 mm thick, made of the same fill that we had previously used to restore cracks in the stone. I then used resins (approved for conservation use) to create a solid base parallel with the top edge. This ensured that the weight would be evenly distributed across the bottom edge, and that any fragile or laminating stone would be protected. I kept this supporting mount flat in shape so that it would be very clear where the original carving finishes and the mount begins.

The relief is revealed

As a result of this conservation work, the original 2000-year-old tool marks and (possibly original) pigments are identifiable. Despite the erosion there is still a lot of detail in the carving which is easier to appreciate now. Whether the relief once encased a fallen soldier, or adorned an important building, we can now clearly see the story of a decisive point in battle – a hard-won moment that promises victory to the Romans.

Legion exhibition

From family life on the fort to the brutality of the battlefield, you can explore the unique stories of Rome's war machine in Legion: life in the Roman army, through objects such as this intriguing relief.

Legion: life in the Roman army is open until 23 June.